A Week in La Alta Guajira: Part 2

A Less Hopeful Take on Local Economic Development and Democracy

Hello readers, as promised, this is part two of my trip to La Alta Guajira. Whereas my last post was much more personal, heartfelt, and dear I say, hilarious, this one is much more inline with my posts about defining what sustainable development means in 2025 in La Guajira.

If you haven’t read my last post, please do here:

And to gain some context on this post, please check out these, especially the last one.

Anyways, I hope y’all enjoy.

What does Local, Sustainable, Community Thriving Look Like?

Here’s my simple (not so simple question) that I’ve been reflecting on towards the end of my fellowship.

In a previous post, I critiqued how economic policy—whether progressive or conservative—almost always centers on increased consumption. I think it’s incredibly difficult to argue against the idea that this growth model is mathematically unsustainable on a finite planet, regardless of innovation, as argued here.

Much of the critique of this stance comes from a political lens: “You’ll never convince people their lives will be better if they consume less. Everyone wants a bigger pie, red or blue—it’s the economy, stupid.” Even as progressives critique free trade and Wall Street, they still use the stock market’s dip as a rallying cry to show how Trump’s policies hurt the economy.

But, as I mentioned before, there is more to politics than material goods. We crave purpose, belonging, and security—whether that takes the form of “secure borders” that keep out a perceived enemy, or more constructive arrangements rooted in community and care.

My time in La Guajira has reaffirmed that current models of economic development rely on the exploitation of natural resources in poorer Global South countries like Colombia—forcing them into export-based economies that keep government treasuries afloat but trap people in cycles of semi-poverty. I came here to explore what could exist beyond that paradigm.

If not extraction, then what? If Wayúu communities reject large-scale renewable energy projects and the compensations tied to them, what do they want instead? And how does what they want fit into the material and non-material dimensions of well-being I outlined earlier?

Punta Gallinas: A Case Study

Situated at the northernmost tip of Colombia and South America is Punta Gallinas. According to my hosts, their grandparents were the first to settle this previously uninhabited territory. Today, the community consists of hundreds of descendants.

In the past, more families farmed the land, but increasingly harsh conditions have made agriculture less viable.

We can ask a basic question: What do people materially need to live comfortably? Food, housing, water, transportation—and in the 21st century, arguably electricity and internet.

We can also ask a deeper question: What are the non-material components of well-being that help people thrive? Having just food doesn’t guarantee happiness. What about networks of care? Aunts and uncles watching siblings' children. Mutual aid. Community projects. People coming together to build houses, roads, and schools with shared resources. And purpose—whether grounded in religion, service to the community, or earning money for personal fulfillment.

This is not the U.S.

My general hypothesis is this: in the U.S., we have enough to live comfortably, but we’ve commodified so many basic goods—water, healthcare, housing—that many still struggle. And beyond that, we’ve eroded the non-material fabric that provides meaning. We lack communal spirit. We lack purpose outside of hateful politics and TikTok-scrolling dinner tables.

The World Happiness Report and other well-being indices show that non-material factors are key. Latin America, despite being poorer than Japan or South Korea, often ranks higher in well-being—largely due to strong familial and communal bonds. So, as an overgeneralization, one may expect the “non-material” components of wellbeing to be higher in a place like Punta Gallinas.

So, back to my central focus. I went to Punta Gallinas to explore three things:

The material economy

The non-material economy

The interaction of the two in producing well-being

The Material Economy

Given how small and isolated of a community that Punta Gallinas is, it's not difficult to track how things move in the material economy.

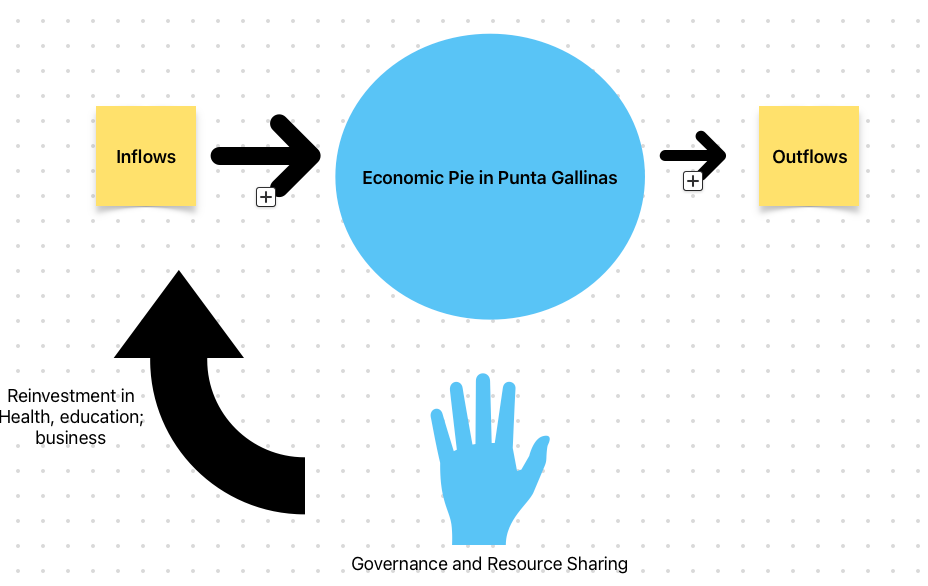

There are three ways that money enters the economy—fishing, tourism, and government aid. Artisanal fishing, passed down through generations, remains mostly sustainable—though population growth and environmental pressure loom.

However, tourism is the economic engine. It's quite simple to think about what tourism brings—new people with money. People spend money to stay in hostels and buy artisanal goods, to eat fish for lunch and dinner, and to go on motorcycle rides in the desert. In the last 10 years, Punta Gallinas has become almost entirely dependent upon tourism for its economy.

And finally, unreliable government contracts supply the social and physical infrastructure of schools and healthcare facilities, and the incomes of teachers, nurses, and social workers.

Yet the town is defined by a scarcity of life-sustaining essentials: water, fresh food, and gasoline. These three items—not housing, entertainment, or tech—make up nearly 100% of household expenses, based on my back of the envelope calculations.

In line with comparative advantage theory, or the economic theory that nations (or places) will specialize in things they are good at to trade for things they need, the Wayúu have always traded to survive. Today, that means a 5-hour round trip—by motorcycle or truck—to buy basic supplies in the nearest town. The prices? Double or triple what you’d pay at a supermarket. This represents a massive outflow of money.

The Non-Material Economy

Punta Gallinas is an evangelical community. There’s no grand church, but there’s no shortage of the so-called "Protestant Ethic." I’ll get to that in a bit.

Everyone is “family”—brothers, cousins, uncles. During my stay, I visited various homes where I was offered tea or coffee. My hosts explained in Wayuunaiki why a gringo in Chacos was bunking with them. A cousin took me fishing morning and evening. No questions asked—except that I cover the motorcycle gas.

Gangly kids ride on their parents’ motorcycles to school if they were lucky. Most walk to school in packs, kicking rocks and talking about kid stuff along the way .

Could this be what the U.S. is missing? Community? Familial connection?

I kept asking my hosts about their family networks. Who are the main cousins? Is everyone close? Most of my questions were met with silence or evasion. On the fifth day, I finally broke through.

“I hate these goats,” my host muttered, shooing them away from the trash pile outside of the house. “They remind me of when they stole our goats.”

When I asked who, she told me more.

“You’ve only seen some of the family. We don’t talk to the others. When my grandfather died, he left hundreds of goats to my father. But my uncle stole them. Everything we had—the boat, the animals—gone. That’s why we live in poverty. So yeah, I want nothing more than revenge. I want to see all those goats disappear.”1

That comment cracked things open. Behind the façade of kinship were deep family divisions—marked by stark inequalities. Some cousins had cars and steady access to food and water. Others were barely able to feed their children more than rice and plantains.

We’re all used to inequality in our neighborhoods and cities: nice houses next to shacks. But within the same family? In the same village?

Can we morally justify that? This is not because some family members were better producers and hustlers in the market. No, this is a non-material issue—a breakdown in relationships that produces inequality.

Non-Material Failures to Provide Material Goods

Punta Gallinas suffers from real scarcity. But it also has the tools to sustain itself. The trucks that exist could deliver goods daily to families. Government-funded boats could be shared instead of claimed by one uncle. Government funds could improve healthcare and education for all, instead of only affecting the few.

But across the stunning desert landscapes are fractured families—each fighting to survive alone.

Instead of a hostel cooperative that shares the costs and profits of tourism, each nuclear family builds their own place. Instead of buying food in bulk and distributing it fairly, every family shops for themselves—paying exorbitant costs.

There’s a refusal to govern resources collectively.

Multiple community members who had lived in cities and returned told me the same thing:

“The biggest obstacle to Wayúu progress is individual corruption and self-interest.”

A leader who receives state funds keeps it for his immediate family. A cousin with a truck charges outrageous fees to take others into town. The material economy—tourism, fishing, state aid—should be enough to support a good life. But those resources are siphoned off by selfish actors.

So what does the Protestant Ethic have to do with this?

The Protestant Ethic generally takes the idea that salvation comes from individual hard work, thrift, and efficiency. It transforms what religion traditionally provides—a non-material respite, despite economic circumstances, into a justification for economic individualism and hustle. I’m not informed enough to discuss how this Ethic shapes Punta Gallinas, but I do think it’s an important indicator of how capitalism has shaped Wayúu territory in La Guajira.

One of the key findings of my research has been that failures to build large-scale energy infrastructure are the result of bad actors upon all sides. The State does not comply with its obligations to protect the rights of communities, the companies and their contractors are uninformed, or worse, conniving to buy off leaders instead of consulting entire communities, and communities themselves suffer from corruption, and division over the associated benefits and harms of these projects.

Stepping Back and Looking from a Distance

Maybe this isn’t surprising.2 But for someone who believes that non-material solidarity can offset material scarcity, this is disheartening.

Capitalism turns us into individual producers and consumers. But here, in a community made of blood ties, I saw the same logic at work: self-interest over solidarity.

So much of my post-capitalist thought has hinged on the idea that people, if they work together, can solve shared problems. But in Punta Gallinas, I saw how distrust breeds distrust. Individualism begets more individualism. The result? Scarcity for many, wealth for a few. And this isn’t even in a region affected by wind farms!

In a recent post, I argued that economic development is designed to enable easy consumption of market goods—at the cost of meaning, collaboration, and connection.

Latin American rural communities have long been known for collective labor systems—mingas, where families come together to build roads, homes, and schools in a beautiful demonstration of collective effort.

But is minga culture dying?

In times of scarcity, do we turn toward distrust and corruption? And in that distrust, are market transactions—despite all their flaws—the only way to ensure fairness?

Because unlike a cousin who might flake on fixing your fishing boat, the market offers something simple: An apple will always cost a dollar.

There’s much more to be said about human nature and how it responds to context. But for now, this is a reminder to myself:

Humans have darkness in them.

They can exploit not just strangers, but their own kin. And in a world where everyone is trying to get ahead, the dream of a cooperative future—of building something better for all—can easily dissolve.

Without trust, we’re left with markets.

And even here—at the northern edge of South America, in an Indigenous community shaped by desert winds—perhaps we have already been grinded into individualist cogs of consumption and production in the capitalist machine.

This is both a translation and a recollection of a quote, so I don’t expect it to be perfect.

As Zach Karmel reminds me, “You’re not gonna like this, but this is nothing new”. I am afraid that I am oversimplifying the dynamics. As traders, the Wayúu have always been apt to commercial transactions. They are also a decentralized society without the hierarchies of power and social order that other societies might have (there’s no president, but rather each family has its chosen leaders).

Love the shout out, but I also don’t believe this one community is the end-all-be-all. Even though it’s a counter-example of the type of world that you want, simply looking up Minga culture on Google pulls up so many examples of communities coming together!

Even if everything sucks and has happened before and conflict is inevitable, community collaboration does exist!