Is the Point of our Lives to Consume?

Tariffs, Abundance, and the Economic/Social policy for the Good Life

This piece is much more informal than other ones and not about La Guajira. I really want to see how people respond to the many claims I make, so please comment. What does this make you think about? What do you agree and disagree about? I’m not an expert, I’m just trying to make sense of things.

As part of my mini-series on Sustainable Development, I am not thinking about just La Guajira but also the globe. I wanted to explore something that has consumed me for years without the benefit of having the words to describe that something- I'll name it consumption. To check out my previous pieces, read

This piece will talk about taxes, books, technology, and somehow have to do with economic development. And it starts with a confession.

Trump has a point about tariffs.

WHAT, no way? Rishab is agreeing with Trump?? Ok hear me out.

There is robust evidence (and already economic signs) showing that implementing tariffs indiscriminately such as how Trump is for goods from Canada, Mexico, China, and other countries, is BAD.

It hurts consumers. We all pay more for goods because prices increase. And, given that our economy is incredibly more interconnected and complex than before, this also hurts producers of complex goods like cars. Even if a Ford car is made in Detroit, it still uses semiconductors from Taiwan, braking technology and screen displays from China, and leather from Italy.

But anyways, let's look at a Trump quote about the tariffs:

“WE WILL MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, AND IT WILL ALL BE WORTH THE PRICE THAT MUST BE PAID”

I can't believe I'm quoting Trump's X post.

Behind misguided policy is an opinion, right or wrong, that an economic policy centered on the consumer may not be worth it, and that the act of production brings intangible value that makes life better. Prices for us may go up when we buy things, but we will find economic and social security in committing ourselves to the factory lines with our fellow Americans. Let me explore this a little further.

We are used to cheap TVs and consumer goods. But Trump chooses to capitalize on on a historical trend: the broader deindustrialization over the U.S. that has hurt factory workers and led to a crisis of identity for many who no longer are tied to producing something of tangible value.

The U.S.'s GDP has grown consistently from capitalizing upon technology growth, making us all undoubtedly (and unequally) richer.

So what have we done with that wealth?

We've spent it on good things (saving for retirement).

We’ve spent it on arguably bad things (more TV streaming service subscriptions, online shopping sprees, and sports betting)

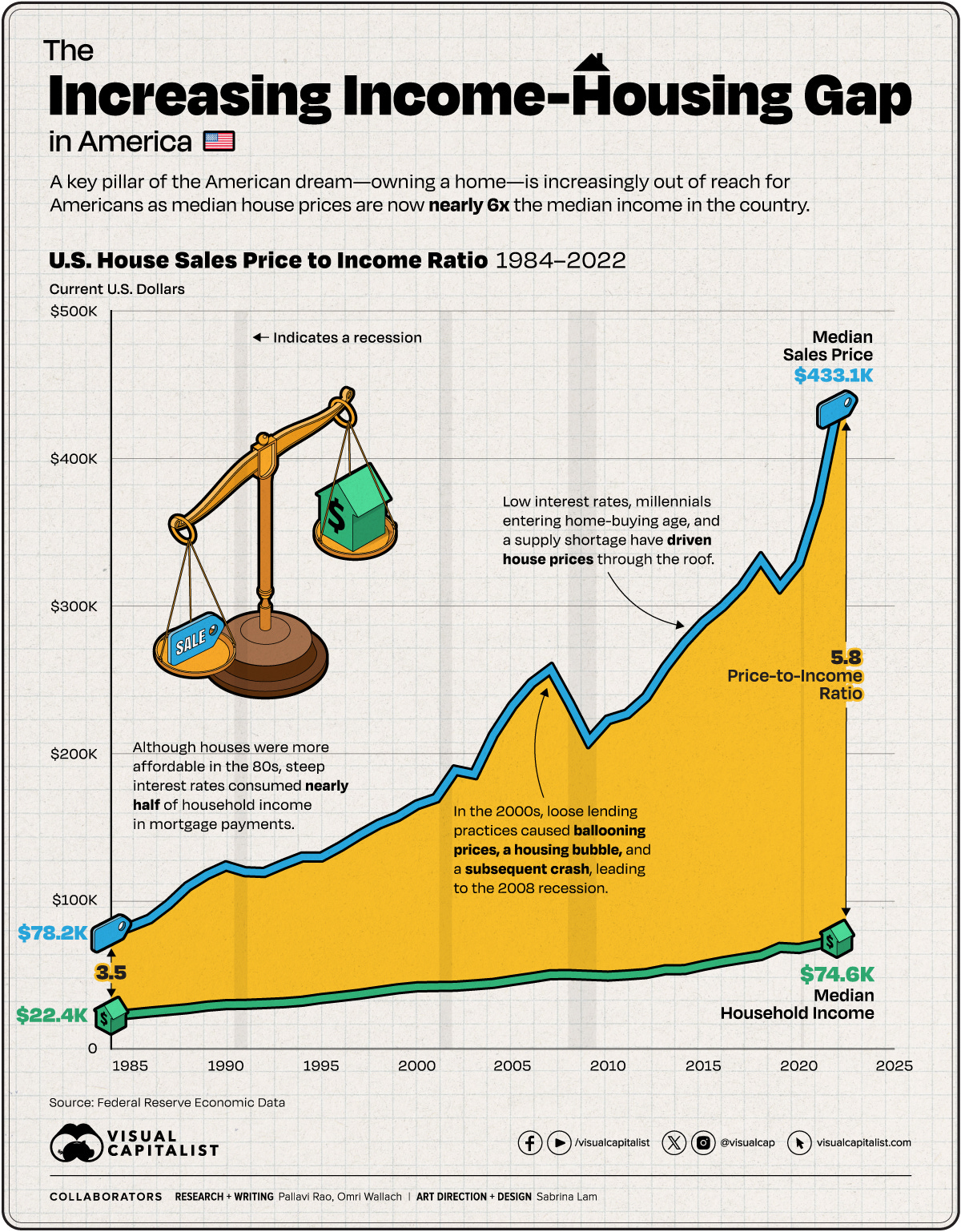

We’ve spent it on necessary things whose prices have spiralled out of control (housing, healthcare, preschool, college debt).

I lay out three arguments based on what I've written so far.

It is more accessible and cheaper to consume goods and services now more than ever (and not only for Americans).

There are goods that genuinely make our life better by consuming them, and goods that make our lives worse.

Necessary services and goods in our lives, such as water and healthcare, are being converted into market items that we must consume, rather than public goods that we can co-create and enjoy.

Abundance: a modern progressive answer

If you've followed me up to this point, then stay with me for this next part. It's not random, I swear. I recently read Abundance. It's the prototypical book that New York Times' readers in California should read if they care about politics. And it's co-authored by one of my favorite thinkers, Ezra Klein. I think it's a great book with a clear argument that responds to the third point I laid out.

“Progressivism’s promises and policies, for decades, were built around giving people money, or money-like vouchers, to go out and buy something that the market was producing but that the poor could not afford.”

“An uncanny economy has emerged in which a secure, middle-class lifestyle receded for many, but the material trappings of middle-class success became affordable to most. In the 1960s, it was possible to attend a four-year college debt-free but impossible to purchase a flat-screen television. By the 2020s, the reality was close to the reverse.”

Ultimately, Klein and Thompson lay out a series of arguments showing that progressives have failed to build and investment in public goods, such as housing and public transportation, because they have given too much power to local actors. Rather, they argue for a strong state that builds clean energy, millions of homes, more trains, more novel drugs, etc.1

They're right within the context of American politics. This is a material case for specific policies, practices, and most importantly, rhetoric, that the U.S. government could use to rebuild institutions, infrastructure, and public trust that government can build big things.

There are few overlaps between Klein and Thompson’s ideologies and Trump’s, but they do share a belief that industrial production (which for Trump may mean gaz-guzzling Hummers and for the other two may mean solar panels and cancer drugs) is the priority for any state.

The key to state development and prosperity is to produce more. Where they differ is that Trump sees production as an end in itself (working Americans means happy Americans) whereas the other two see state production as the key to consumer satisifaction (albeit through public, necessary goods like healthcare, public transportation, etc).

The purpose of Abundance was to see how to make government work better, not to dream of a politics where economic development is in line with values of social justice, community, and building trust between humans (which I believe ultimately make the "good life"). That is what bothers me about Abundance. We are beneficiaries of a society where everything is materially easier. But do we feel purpose? Meaning? Does a world where good things are easier to consume make us better, more prosperous humans? I’m not so sure. Even if the state is the provider of green, affordable goods, we are still living in a society where we are passive consumers.

Hopefully, at this point, it's clear that I referenced Trump and the contrast between producing and consuming for a reason. When I think about the future I want, I do imagine clean energy and affordable healthcare. But I also envision non-material things that Trump’s so great at selling. It's not Trump’s nationalism or xenophobia. It’s a feeling of deep trust with our neighbors, choosing to prioritize collaboration and peace, and chipping away at inequality.2

Here’s a TLDR of what I’ve just written.

Economic development in the U.S. and in the rest of the world is incredibly reliant on consumption. It's what fuels economic growth and makes people richer by most standards. But I think that there are environmental, social, and political costs of consumption that ultimately hurt us more than consumption helps.

Ever-growing consumption, even if it consists of renewables, cannot sustainability continue on a finite planet. Humans co-creating things, movements, and moments, not consuming them, is what makes us feel connected to something bigger. And politically speaking, an economy driven by consumption is one that turns us all into passive TikTok scrolling conformists that never question the status quo.

Let's dive into what I'm saying.

A Personal Anecdote

There have been many culture shocks from my time in Colombia. But maybe one of the most surprising ones has been a universal trend across the world in poor and rich countries. I see a younger generation, and increasingly an older generation, addicted to smartphones.

I don't think I'm a boring person, but there have been multiple occurrences when I have not been able to have more than 20 seconds of conversation with someone before they turn away to respond to some WhatsApp message. Or, when I want to start a conversation, but the other person is completely immersed in their TikTok feed. Where even though I don't have TikTok, I know that Doechii's Anxiety is the most sampled music right now because I hear it literally everywhere. It's terrifying. And it's not just Colombia.

But the purpose of this piece is not to complain about how smartphones have corrupted us--it's to demonstrate that the time we spend consuming content is time we don't spend creating experiences and producing meaning out of our own lives. Economically, our time on social media is great for any corporation trying to sell new products by bombarding you with subtle ads that they pay for from Facebook's extensive database on your demographic profile (expectant mother? you'll get baby crib ads).

So much of economic policy is built to maintain effective demand--essentially the notion that people keep buying things because they think that they'll have more money in the future to pay for it. So we will continue to spend more time doomscrolling on X, shopping for Temu shirts made in sweatshops. And we will spend less time thinking creatively and eating dinner with other people.3

I try to journal each day. And I don't always succeed. I told myself I would stop watching Netflix. And now I lose sleep because I have to watch two episodes a day of a show I enjoy. I go on Instagram almost every day for a few minutes, while my conscience self criticizes myself and my subconscience relaxes into receiving dopamine. Heck, I've been trying to read Hegel, but only between the TV timeouts of March Madness basketball games. We're all struggling. And an economy built upon consumption is going to continue to make us struggle.

I'm also choosing to not write about all the gifts of consumption, especially with technology. We are more connected. I know people whose jobs are miserable, whether due to physical strain (dangerous mining) or pure boredom (security guard). And a phone helps pass the day. It makes life bearable. And of course, consuming things with other people is fun, whether it be a restaurant meal, comic book conventions, or newly released movies. And that's ok.

“Ok so what are you actually proposing, Rishab?”

I don't have a silver bullet. In the case of the U.S. and Trump, reigniting obsolete manufacturing jobs in the Rust Belt is not a viable option. To Klein and Thompson's point, governments should be better at providing basic and goods and services for people instead of them letting them get sucked into an extractive, low-paying economy where you can't afford to get a babysitter to care for your child.

But what is our economic policy for community?

Hopefully one in that when a community faces a dire need in La Guajira, they can have access to state resources to build their own solution, rather than being subject to austerity policies and starvation or passivity and over-dependence.

What is our development plan for solidarity?

Hopefully one in that we spend less time consuming goods and more time supporting each other and creating non-economic value (after all, it takes a village to raise a child and a community garden).

What is our economic policy for increasing human agency over decision-making?

Hopefully one in that participatory democracy, however inefficient, can weave networks of justice and meaning for people.

I want more people to think about these questions. And I want less people to be on their phones. But I have to go, the season finale of my show is waiting.

You should definitely read Abundance if you’re thinking about American governance in the medium term and how to make things…well…better. And Mariana Mazzucato’s The Entrepreneurial State to debunk claims that any government intervention is bad for innovation.

This feels undefined, too good to be true, a dream without a roadmap. And that’s right. I want to get these thoughts out now, but I hope to develop them more fully with time.

Shout out to my friend Brian for reminding me of the importance of shared connection over food. And check out The World Happiness Report.

Ok cool I'm glad someone else is having trouble swallowing anti-tariff arguments, and that someone is you -- with the literature review and developed analytical muscles that can explain your feeling of unease. My main takeaway from what you wrote is a questioning of why :"consumption = good" is the equation everyone takes for granted before debates even commence (you also convinced me to move "Abundance" to the top of my reading list). I stewed on this for a bit, and realized how troubling it is that tariffs get critiqued from this pro-consumption starting point. I read an op-ed by Oren Cass (top dog at a right-wing think tank) and was struck by how he hit the exact same notes as other, Democratic, criticisms. Sentiments like "obviously China gets a tariff," "this will hurt Americans' grocery bills," "intervening in the globalist system is bad because of Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression." In an era of polarization, it is eerie to see consensus from thinkers supposedly opposed -- remember Dick Cheney stumping for Harris? This happens when there is a fundamental assumption that the establishment leaps to defend. People assume that because The US has benefitted economically (and unequally) from open trade, The US has benefitted holistically from open trade. I LOVE that you acknowledged Trump's skill at producing non-material feelings; too many people who disagree with him ignore the charisma he exchanges with his base. It is pointless to analyze why Trump does X thing, but I do think he acts on a sense that this current moment's dopamine draws: March Madness, TikTok, and Shien clothes, leave one with a dissatisfied itch in your head when you switch off your device and roll over to sleep.

Maybe a place with 5% of the humans should not consume 25% of the things there are (rough numbers pulled from google AI, but you know it's true). I write these words, but I have no concept of what a less voracious consumer appetite would look like in my life. I actually find I lack vocabulary to think in this way, and I'd imagine many others who are troubled by Trump's unflinching quid-pro-quo extraction feel a similar loss of words. "Tariffs are bad because they could ruin an oh-so-comfortable status quo," we say.

Success here involves walking a very difficult line. I wish to criticize Trump's destruction of our system without ignoring the flaws in what we have. Maybe, in the shake-ups that come, we'll find the silver lining to our new reality.

(Not that I truly believe Trump has the stomach to see these actions through to their painful end. There will be another sensationalist turn in the story, simply because the Tik-Tok culture he saved from prohibition cannot abide by a stagnant narrative.)

You honestly did a better job at making me understand the tariffs situation (my brain shuts off at anything economics-related) than anything else I’ve read to try and get it, so thank you for that.

I was talking to my mom today and she was giving me the “you need to delete social media” spiel, and she said she had to get off the phone to go do some garden work. 20 minutes later I called her back to ask something random and I found her in the same position I had left her in—she had gotten distracted by Instagram Lol.

One of the most frustrating things about this overconsumption of social media and screen time is that the knowledge that it is bad, because we know that it is bad, does very little to actually stop anything. Overconsumption in general is affecting overall discipline. And like you say it’s getting in the way of the very thing that is necessary to repair what’s left to be repaired in this world, which I think is community building.

Idk, I wish I had more hope and less knowledge. The more I know the more hope I lose.