Energy, Economic Growth, and Well-being

Some contradictory thoughts about where society is going.

First, this piece is too long for email! Click on the link to read it in Substack!

I wanted to respond to a previous post on sustainable development. Please read!

Most of my writing is making sense of disparate things, and that's what I'm doing here in the most informal way I can.

I'm going to take this piece to devolve my thoughts (which as of March 2025 are still evolving), in relation, to, everything. Ok well, unfortunately spilling all the tea would be an incredibly tedious and impossible task full of blank spaces where I say, "Well I don't really know". But what I can do is supplement a prior piece taking on the fallacies of Sustainable Development in La Guajira in the Global South.

Food for thought:

I care about climate change. I care that non-human life suffers at the hands of us. I also care that people can live fulfilling, thriving lives in stable ecological conditions. That's not too much to ask. So, as I throw these links at you (which I encourage you to check out), I hope it provides a glimpse at my frustration at where things are.

1. Jason Hickel shows that economic portrayals of extreme poverty reduction have incredibly flawed methodologies, and in many places extreme poverty has increased or decreased only slightly, even as we’ve been in the “golden age” of progress.

"The BNPL data indicates that the story of global poverty over the past few decades is more complex, and more troubling than existing narratives allow".

“Historical data on real wages since the 15th century indicates that under normal conditions, across different societies and eras, people are generally able to meet their subsistence needs except during periods of severe social displacement, such as famines, wars, and institutionalised dispossession, particularly under European colonialism. What is more, BNPL data shows that many countries have managed to keep extreme poverty very close to zero, even with low levels of GDP per capita, by using strategies such as public provisioning and price controls for basic essentials.”

2. Michael Mezz outlines 5 cases of the seeds of non-extractive, community and human rights forward projects across the world, including worker cooperatives, measurements beyond GDP, and commons-based digital resources that break the monopolies of big tech.

3. CERA Week, the world's largest energy conference hosted in my home of Houston, TX, projects the continued expansion of Liquified Natural Gas and Oil, powered in large part by the U.S.'s "leadership" in increasing fossil fuel production. Drill, baby, drill, not just according to Trump but also according to most fossil fuel companies’ boardrooms. It’s a good reminder that the fossil fuel world keeps chugging along.

4. IEA World Energy Outlook 2024 reveals a sobering reality.

"despite record clean energy deployment, two-thirds of the increase in global energy demand in 2023 was met by fossil fuels, pushing energy-related CO2 emissions to another record high."

I encourage anyone to check out these links and learn more about what’s going on within the global discourse around energy, poverty, and sustainability.

What is happening on a global level

I'm going to set aside geopolitics for this piece. While I would love to speculate on what U.S's friendly relationship with Russia means for E.U. Security or the role of tariffs on affecting U.S.'s hegemony as the world's reserve currency, those topics are frankly out of my league. Most economic topics are out of my league. But, in my best conscience, I can seek to understand the basic building blocks that make up what we call "economic progress".

In my last piece, I argued that "sustainable" development through the extraction of natural resources in Latin America is a continuation of colonial tendencies that enrich Europeans and North Americans while impoverishing and polluting people and ecosystems.

I also understand the basic rules of supply and demand.

The price of coffee is at an all-time-high due to insatiable demand and climate-change related weather disruptions in Vietnam and Brazil that have reduced supply, so growers in Colombia have sought to grow more coffee.

And finally, I understand the fundamental role that energy and minerals play in what we call human development. Energy, whether through the form of the goop of dead dinosaurs or the electrons freed by the sun's rays, is everything. It makes work easier. It makes life livable in places that are ever-hotter, regions where life is difficult if you don't have access to a motorcycle or electric boat or giant tanker to ship in goods. Energy, in the form of fossil fuels, molded this beautiful, nasty, twisted human world over the last 300 years.

A Steady Incline, or an Impending Cliff?

The last three hundred years have been the most transformative, materially speaking, for humanity and for the Earth's surface.

Earth's population has gone from less than 1 billion humans to over 8 billion in just three hundred years. Forget the fact that we've octupled: think about 7 billion more human bodies on the Earth than what the Earth held earlier. And, alongside population growth and economic growth has been the proportionate rise of energy consumption in fossil fuels.1 The scary thing about growth however, is that it is exponential. According to the International Energy Agency, the world's electricity consumption is set to grow at 4% over the next three years, which would mean that electricity demand if forecasted over the next 17.5 years would double, along with a roughly 20% increase in population growth that would get us to 10 billion people.

The fishing village: An excerpt on growth

I'm going to pose a scenario here. Pretend you were a fisherman, and there were 1000 fish for your community of 10. Every year you fish 4% more. Say your community grows at around 2%.

Year 1, and your community fishes 5 fish.

Year 19, and your community fishes 10 fish. Nothing to worry about.

Year 36, 20 fish

Year 54, 40 fish

Year 72, 80 fish

Sure, it's increasing, but the pond is fine. You have plenty of fish.

Year 100, 250 fish.

Year 150, 1800 fish.

Year 300, 644127 fish for 3800 for us humans.

That doesn’t seem right. How many fish did we start with, again? 1000!

Real life does not work this way. Humans innovate! We farm fish, we genetically modify fish, we feed them fertilizer. We expand and conquer new ponds, even if other people had been sustainably fishing them before for centuries. We grow, and we grow, and we keep up production. That’s the narrative we tell ourselves.

This example is not a treatise on Malthusianism. I'm not saying we're all going to die of hunger because of population growth. I'm saying that humans have created so much abundance for themselves, and that abundance comes from the expectation that we will continue to exploit a resource.

Energy, the foundation of it all.

When it comes to energy, that picture is clearer than ever. Energy use is highly correlated with human well-being.

Modern life is built on energy, and my time in La Guajira has been a humbling reminder of how access to reliable electricity growing up has allowed me to do my homework at night, go to school, text my friends, bear hot summers, and do almost everything in my daily life.

We can now ask ourselves, at what point do we have enough fish? Enough energy? If the top 1% of the world held 43% of the fish, that means that even though we fish more than enough to feed our humans, many go without eating. Or in Oxfam's words,

"The richest 1 percent have more wealth than the bottom 95 percent of the world’s population put together, new Oxfam analysis of UBS data reveals today ahead of the annual UN High-Level General Debate."

"The top 1 percent own 43 percent of all global financial assets.”

Yet, with this abundance, 1.18 billion people in the world are in energy poverty, meaning that they effectively do not have access to affordable electricity ([UNDP]. In international development discourse, organizations like the UN are spearheading efforts to increase electricity access in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, and it is necessary that people gain access to electricity and refrigerators and other necessary items that can store important medicines, preserve foods, and contribute to well-being.

But what surprises me is the insatiable appetite that rich countries have for consuming energy. Renewables, especially solar, have exploded in popularity, becoming by far the fastest growing electricity generation source in the US. Yet, with the rise of energy demand from data centers and industrial sectors, some states report that all of the renewable energy being put online is only covering the new demand, rather than reducing the demand of natural gas. Of course, we should expect renewables to increase in terms of the proportion of energy generated, but the trek is long and slow.

We may not be reducing how many Oreos we eat each day, but now we're drinking a glass of green juice for breakfast. Does that make us healthy?

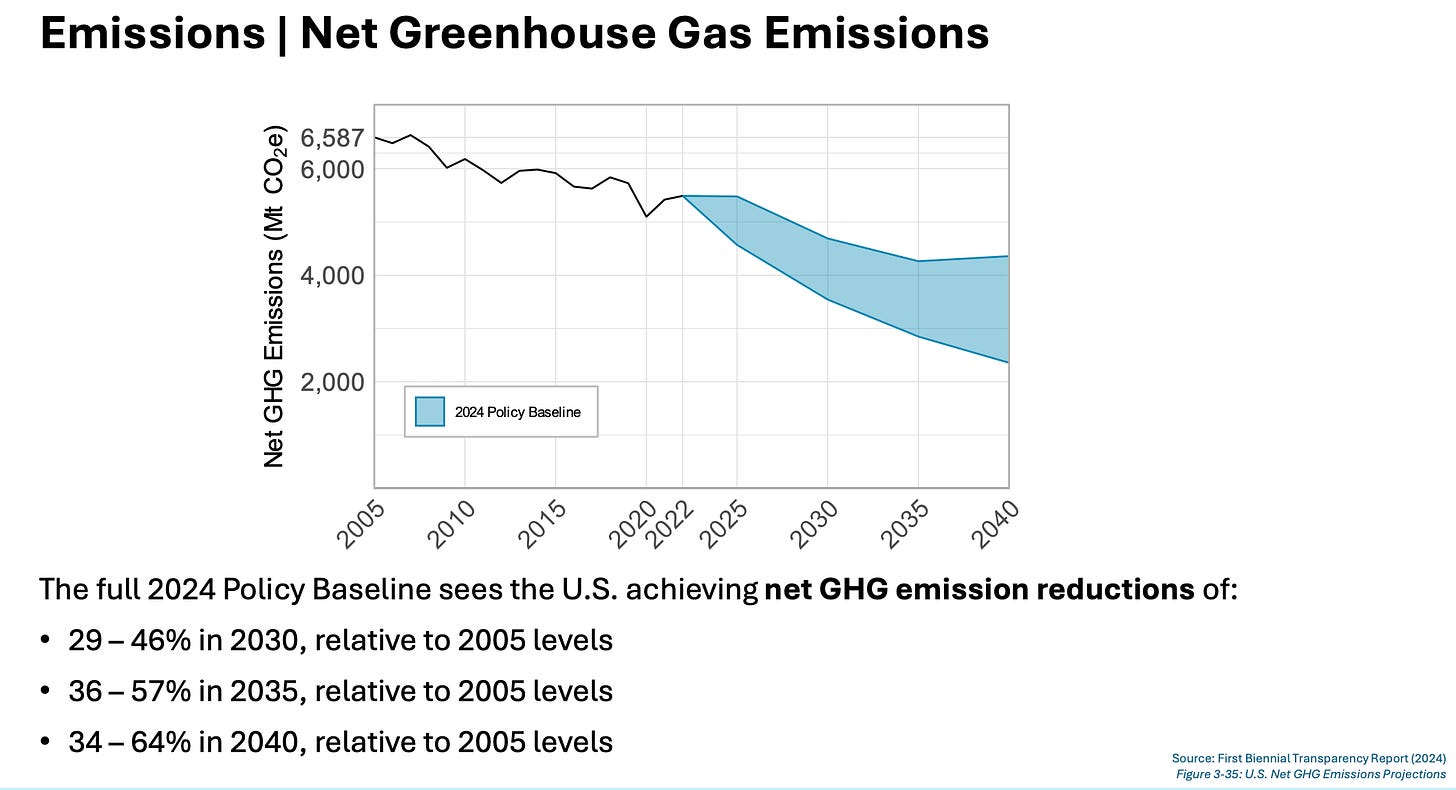

In the U.S., our CO2 emissions per capita maxed out at around 21.4 per person in 2000. After 23 years, 2023 emissions per capita were 14.1 tons per person. And based on our current trajectory, we'll be lucky to reduce emissions by another half by 2040, although this gets no where near close to the Net-Zero emissions that we need to get to as soon as possible.

Obviously, this shorthand math doesn't account for the politics (both good and bad) which affect the rate at which the U.S. will decrease emissions. But it pretty damn well represents how difficult it is to decarbonize when we use so much energy.

So the answer is to increase energy efficiency, no? Sigh. I wish my reflection could end there, that countries like the U.S. need to have better energy efficiency programs and we'll be on our way.

Do you see the problem?

It's not just that we're not moving fast enough. That's apparent. It's that within a system where we are continually demanding new electricity and continually buying new things, we are also trying to reduce fossil fuel use.

We are in a system where cars continue to get more efficient in miles per gallon but where we also sell more cars. We are in a system where smart appliances are energy efficient, but we still need to buy more of them.

What I'm getting at is that increasing renewables won't solve the climate crisis. We need to attack the emissions at their roots. The insatiable growth of consumption.

These questions terrify me. In college, I became familiarized with the field of Degrowth2, which argues that rich nations need to consider shrinking their economies if they hope to reduce emissions and the environmental degradation that is destroying our planet, our non-human neighbors, and the Global South. This piece doesn’t aim to properly analyze Degrowth, but it’s a word to keep in mind.

The Contradictions of the Consequences

However, I don’t want to gloss over how radical the consequences of understanding the previous section would be.

If people buy less cars, what will happen to jobs in the EV sector?

If people buy smaller homes, what will happen to "green" steel manufacturing plants.

If we can't have Oreos and green juice, are we doomed?

I cannot forget to mention countries like Colombia because they are directly affected by all of these processes.

BAD: If the European Union demands less coal, and coal prices drop, then the biggest employer and source of GDP in La Guajira will disappear, leaving thousands of workers without incomes.

GOOD: If people buy less EVs, then copper demand won't be so high, leaving pristine ecosystems and Indigenous land defenders in Bolivia and Ecuador from being ravaged by multinational corporations.

GOOD: If people stop demanding new models of iPhones every year, then child labor in the DRC for the mining of critical minerals might decline.

But in all of these scenarios, the good and the bad are intertwined.

Less EVs may mean more emissions.

Less copper and less coal means less government funding for social projects.

Less iPhones means that there will be fewer manufacturing jobs for the rapidly growing Chinese middle class.

And if there's less industry, less jobs, less energy extraction, less exploitation, then what will humans do? Where will they get the money to pay for basic goods and services?3

There's no easy answer to all of this.

But within all this confusion, I hope that we can agree on a few things, with each point becoming a little more controversial.

All humans deserve a dignified life. One where they can access electricity, food, water, housing, healthcare, and community.

The world's economy depends on economic growth, and economic growth depends on energy extraction. The Global North has grown a lot because they have exploited energy (and the land and labor of the Global South) for centuries. Economic growth is the one belief that all politicians share, that accountants can rely on.

Drastic inequality, between and within countries, is bad. It is immoral. It increases environmental exploitation as the rich take the poor's resources. Most importantly, it demonstrates that economic growth has not actually improved the lives of everyone on this planet, at least with how unequal it has been.

As the world transitions to "green energy", we cannot simply focus on making more of the "good" solar and wind energy. We also need to think seriously about burning less "bad" fossil fuels and reducing clean energy mineral mining. That means policies that truly consider making material sacrifices in rich countries.

Policies that choose to defend local ecosystems and communities, such as La Guajira, may reduce economic growth for society at large. They may result in job losses and everything bad we associate with recessions. There are costs. But maybe that's what our non-human animal and plant neighbors, communities defending their livelihoods, and future generations ultimately need to survive.

If you read my last piece, then you have to imagine the consequences of what such a future would look like, both for the U.S. and for "developing" regions like La Guajira.

If the U.S. bought less Colombian bananas, coal, and flowers,

Would their peaceful alliance fall apart as Colombia fails to export enough goods to pay off its debt with the U.S. and the World Bank? Would both countries invest more in military forces, and would worldwide violence increase as more countries stop participating in Global Economic growth?

Or, would this offer the autonomy, spur the land reforms, and give Colombians the breathing room to choose what the good life looks like for them? That instead of producing and selling flowers to pay for healthcare, they enact more community health clinics and food sharing programs? That environmental conservation helps them generate renewable timber and bananas that sustain well-being?

I'm not arguing that the world is going in one direction or another. I also believe the world is much more complex than these two paths. But I do believe that the second world is possible, if humans choose to make it happen.

Mombekova, G., Nurgabylov, M., Baimbetova, A., Keneshbayev, B., & Izatullayeva, B. (2024). The Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Population and Economic Growth in Developing Countries. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 14(3), 368–374. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.15614

Some of the authors I’ve enjoyed reading:

Kohei Santo-

Saito K. Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism. Cambridge University Press; 2023. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108933544Jason Hickel: Hickel, J. A Theory of Abundance. Real-world Economics Review, issue no. 87; 2019. https://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue87/Hickel87.pdf

For example, a research study showing that many economic indicators increased with the presence of mining in an Ecuadorian town, except for teenage pregnancy and school drop-outs.