Finance, Power, and COP16

What international cooperation and community resistance tells us about power

Have you voted? Have you gotten your friends to vote, you know, the ones that don’t really care, but you took 5-10 min to talk to them about why this election is important to you? Please, I’m begging you.

Leaving COP16 more lost than I started

This piece has been consuming me for a while.

I walked out of my last event at COP16 distressed, embarrassed, confused, and utterly alone. In a week full of mostly fruitful conversations, I was consumed by the pessimism raging through my blood and paralyzing my brain. I had just spoken in a big event during a Q+A to share my thoughts on the energy transition. I butchered what I wanted to say. I'm pretty sure it sounded ignorant, dismissive, something an American who struggles with Spanish would come up with in a room of thoughtful activists. I was the only person who people didn't clap for, who people didn't come up to after to discuss collaborations.

I immediately went on a walk to a park 20 minutes away. I needed to be alone in my solitude, my loneliness, my lack of language to describe the emotions I had been feeling and the logic I had been developing over the last week.

But maybe my inability to express my rambled thoughts in a 2 minute speech in Spanish is representative of the larger problem here--I'm getting stuck in systems.

And it will surely be poorly written. But I have to try to wrap my head around this confusing world. And there's no better place to do it but in the clouds on the flight back to Riohacha.

If you need a quick primer on COP16, I encourage you to read my last piece.

In short, COP16 is the bi-annual global biodiversity conference run by the United Nations with the goal of curbing biodiversity loss across the world.

In hosting COP16, Colombia wants the conference to be interactive, participatory, and inclusive of the environmental voices marginalized in traditional negotiations. To accomplish that, they took the approach of hosting the Green Zone for public participation, and the Blue Zone, where delegates from 180 nations meet to discuss policies and implementable strategies.

In one sense, the Green Zone is a beautiful path to democratizing environmental knowledge and participation in the most important crises facing humanity. After all, it's not politicians that face the consequences of environmental degradation, but the citizens.

Around 30 minutes away by taxi or bus was the Blue Zone, a highly secure conference resembling the corporate headquarters of a Fortune 500 company, in which the "real decision makers" would come to the table for 10 days of intense negotiations.

I put "real decision makers" in quotations because this piece gets the root of what makes international environmental cooperation so incredibly necessary, contradictory, and perhaps even counter-productive. Let me explain.

The Green Zone: The Voice of the People

Spread across the city center of Cali lies La Zona Verde, a sprawling set of universities, cultural centers, office buildings, concert halls, and of course, the flagship public park of the city. While the UN did not approve my accreditation to access the Blue Zone, the COP16 organizers somehow did accept my request to gain a Press VIP pass (under the well-established personal blog website, Substack) to access all conference events in the Green Zone.

After graciously being invited to participate in two youth forums (Shout out Life of Pachamama and Global Youth Biodiversity Network), the official COP16 order of events started. For me, that meant attending 4-5 Green Zone speaker sessions and panels every day with a notebook and audio recorder in hand.

On 9 am on Monday, I rushed to my first event, hosted by the Ministry of the Interior of Colombia on their policy of Prior Consultation--you know, the one I've been studying for over a year. However, in somewhat of a representative fashion for the rest of the week, they failed to show up. And, over the course of each day, at least 2 events run by governments and big NGOs were marked by a patient crowd waiting 20 minutes before the building staff apologized for the no-show. If the Green Zone is the zone of the people, and these panelists are compensated for signing up to speak, their absence demonstrates the point I'm making. In some ways, the Green Zone is performative.

Let me be clear--there were various Green Zone events hosted by passionate, well-intentioned activists and community organizations that truly did want to foster connection between the attendees, such as...

A participative 80 person session to generate a list of actionable policy demands for an Eco-feminist future in Colombia

A lecture on how to connect investigators to communities through participative community mapping ad social cartography.

A discussion on how modern finance privatizes community land and that environmental solutions should prioritize protecting the "Commons" of community-controlled natural resources.

Various panels on how local environmental conservation is contributing to peace efforts that rehabilitate former paramilitaries and reconstruct broken communities.

A protest against the U.S. funded military base that Colombia plans to construct in La Gorgona, a Pacific Island known to be a whale haven and the homes of thousands of people.

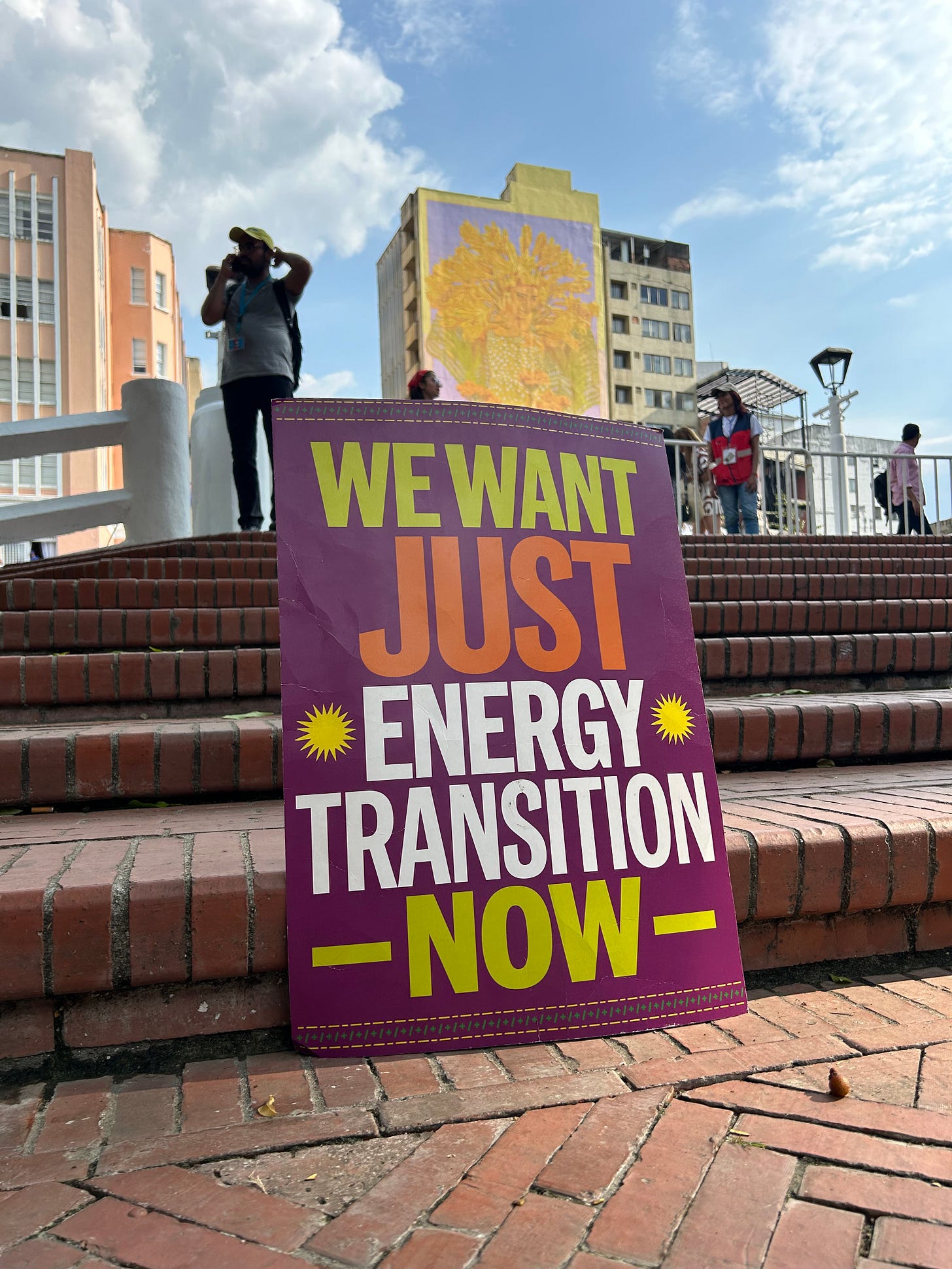

And of course, various discussions around how local actors define a Just Energy Transition.

But the thing that has stuck in my mind from the Green Zone has been the fiery, desperate, furious calls for justice from communities affected by environmental degradation at the hands of their governments and multinational companies.

For instance, Mercedes Yovera Espinoza, a community leader in the fishing region of Peru, discussed how the oil company Repsol's oil spill on the Peruvian coast in 2022 and their subsequent inaction to properly remediate the harms has completely devastated the thousands of fishermen, tourism operators, and indigenous communities dependent on the richness of the Pacific.

Whether it be coal, gas, oil, or the various metals and minerals that power our insatiable desire for consumption and growth, Eduardo Galeano's assessment of the Open Veins of Latin America remains as true as ever. And it is the rural, largely Indigenous communities that bear the cost of societal "progress".

There's a morally easy answer here--STOP DRILLING. Latin American governments need to strengthen environmental legislation and litigation against the damaging extraction of natural resources. They need to offer the service of prior consultation (or in my opinion, free, prior, and informed consent) to communities that are on the frontlines of future action.

Of course, there's some complications. For all the movement around closing mines such as the Cerrejón coal mine in La Guajira or other fossil fuel production centers, it is also the case that national governments have an economic interest in continuing production because its associated royalties fund much of governmental social programs (no coal, no healthcare?). But putting that problem aside, much of the discourse at COP16 is on the same page--we need to protect sacred, biodiverse lands from the plunder of a fossil fuel-based economy.

By now, you've probably noted the power and limits of the Green Zone.

POWER- when local leaders come together, they build networks of resistance against the various exploitative practices affecting their local lands and waters.

LIMITS- while these local crises raise public consciousness, they don't reach the Blue Zone of decision-making.

The Blue Zone: The Voice of Power

Any international conference has to do a few things.

Get a bunch of powerful people and interests to agree on a common language of action and commitment (such as the Kunming-Montreal Protocol of 2022).

Come up with mechanisms to implement programs and accountability measures on the international level.

In the case of COP16, it means

1) getting countries to share specific plans about how to address biodiversity loss,

2) worldwide banking institutions coming up with the financial architecture equipped to direct funds to biodiversity and climate efforts, and

3) finding pathways of governance to involve local, regional, and international levers of power.

By November 1st, the end of the conference, I'll have a better sense of whether COP16 achieved the first two goals. But as for the third goal, my access in the Green Zone has made me skeptical about the possibility of its actualization.

I'll name two reasons why.

Biodiversity protection and capitalism are contradictory forces

Global finance, governance, and institutions, while necessary for coordinated action, are the reason why local voices are rarely heard.

1) Biodiversity, capitalism, and the energy transition

As I've explored in other pieces, La Guajira, Colombia is so interesting to me because its the frontier region of expansionary capitalism. That is, while in the U.S. we are generally on the same page about developing our "economies" through fossil fuel extraction, heavy industry, and most importantly, the constant search for new forms of production (new products, new industries, new corporations, new investments), La Guajira, is in one sense, free from that. While they suffer an extractive past and present, much (though of course not all) of daily life is about protecting the status quo of the Colombian coastal lifestyle (time, friendship) than expanding the means of production to earn more money. This is most pronounced in Wayuu territory, where many communities do not envision plans for future-focused "development" but rather "planes de vida" for the well-being and maintenance of community structures and norms.1

This piece is not arguing whether one "way of life" is better than the other, but rather to say that environmental and territorial protection is as much an issue for the poor as the rich, whereas in the U.S. we associate biodiversity protection with rich white birders from New Hampshire.2

So where does capitalism and the energy transition fit into this? Well, in order to transform the world economy as rapidly as possible in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss, private and public finance has been unleashed to target high-impact, scalable solutions. For instance, in La Guajira that means that the Colombian government has been auctioning off licenses to multinational companies to build the electricity that can potentially power much of the country. Which means building gargantuan wind and solar plants on broad swaths of "undeveloped land". Which means going into Indigenous territory and disrupting local ecosystems through infrastructure development on fast timelines for profitability sake. Which means that a slower, non-development-based way of life, is in jeopardy for thousands of Wayuu.

In other words, sometimes the climate solutions we need may negatively impact the ecosystems and people that need the most protection.

I'm studying just energy transitions for this very reason--how can we use public policy, community participation, and clean energy to improve the autonomy, participation, and sovereignty of the world's indigenous, rural, and poorer populations?

But if you talk to most climate techy folks (or emissions' realists), the reality is that we need to construct a bunch of huge infrastructure to sustain a massively growing industrial economy in today's world. And we're going to need sacrifice zones to provide the nickel, cobalt, copper, lithium, electrons that power the world's cities, especially in the "developing" world. All these resources have to come from somewhere.

2) Global and Local Dissonance

The dynamic I'm describing above is in essence a dissonance between

global goals and capitalist tendencies; and

local realities and resistance.

The world that Mapuche people in Chile want is often not one filled with extractive lithium extraction to power the billions of electric cars that the world needs to keep up with climate goals.

The world that community members in Totoral Chico, Bolivia, desire is not one where massive mining deposits for precious metals are deployed to supply the world with key semi-conductor components for more energy-efficient materials if their water and their land becomes uninhabitable as a result.

Many Wayuu people in La Alta Guajira do not want 200m tall wind turbines that send clean electricity to Bogota and Medellin at the cost of their territorial sovereignty, their connection to local wildlife (bird migrations), and spiritual connections to the wind.

In essence, when we truly talk about the clean energy revolution, much of the brunt is necessarily put on the communities that have been screwed over the most. The world benefits, but at the cost of a vulnerable minority.

So where do we go…

At COP16, it felt like local activists were calling for much needed justice, both against fossil fuel extraction, illegal logging, and expanding livestock production (overall bad), but also against clean energy materials mining and renewable energy production (overall good).

A new UN report says that more renewables are being built now than ever. It also says that emissions are still rising, because energy demand is rising faster than renewable use. It’s getting worse, not better.

So maybe, just maybe, we need to be more creative in the Blue Zone spaces to not just think about how to generate more better, but rather use less.

And if we actually think about that idea, it has fundamental repercussions for the system of global capitalism.

It possibly brings unfair sacrifices for much of the urban world, as they give up access to cheap electricity. But it may finally bring justice to resource-rich land defenders.

There's really no good route.

And I hope someone can prove me wrong.

Just want to add that reading

’s piece about Climate Finance is inspiring--there are movements to connect global finance to local forces without the necessity of scale. And of course, ’s Paloma who reminded me that there’s never easy fixes to complex problem. But the joy of the work lies within the resistance. We should always fight for someone, something we believe in.Good luck reading this mess, and please ask questions about things you’re curious about or interested in!

To enacting utopia through resistance and the defense of territory,

Rishab

Of course, it’s very complicated and impossible to generalize. So take what I’m saying with a grain of salt.

This is not the whole story. In general, climate change mitigation and biodiversity protection go hand in hand. A slower warming climate means less species will lose the ability to survive in their habitats. A more biodiverse ecosystem typically absorbs more carbon. So I’m not saying that climate action and biodiversity protection are opposed, like those hard core preservationists. I’m just saying that there are tradeoffs to the specific way in which we think about climate action through clean energy that should be taken into account.